DIDACUS RAMOS

Interview

Didacus Ramos has careered his way through some interesting professions. As a filmmaker he worked on a Tippi Hedren film and helped set up the first cable station in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. As producer on a documentary he dealt with NASA, Pan American Airlines, State Departments, etc. Didacus spent years in city planning and now specializes in water use.

Didacus Ramos has careered his way through some interesting professions. As a filmmaker he worked on a Tippi Hedren film and helped set up the first cable station in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. As producer on a documentary he dealt with NASA, Pan American Airlines, State Departments, etc. Didacus spent years in city planning and now specializes in water use.

“There is no one way to solve our problems and meet our challenges. The biggest thing that requires is for us to release the past and embrace the future. I know, sounds rather New Age. But, it’s true. We have to let go of the how and why we got here. And, we have to embrace possible solutions—knowing that some are not going to work.”

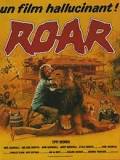

Monty – We met you on location of a film starring Melanie Griffith, Tippi Hedren, a lot of lions, tigers, and an elephant. Tell us some of your experiences working on ROAR.

Didacus – ROAR was my first feature film since graduating from USC. I had already worked in the film industry in San Francisco and Israel for several years before USC. But now I was getting into the big leagues. The best thing about ROAR was the crew. I met great people who also were just looking for a break. Wow. What a challenge. Meeting Tippi was like meeting an icon. You could see just watching her that she was playing chess while the rest of us were playing checkers.

Melanie was just starting out. She turned 21 while I was working on the film. She was already decades older in so many ways. She really wasn’t living on the same planet as the rest of us. The tigers, lions and elephants…well, that was ROAR. I should have been scared. But, honestly, Monty told me that the animals can sense fear—so, don’t even think it. Almost six months of not taking a leak. That hurt.

Tippi Hedren’s Shambala Reserve is home to many big cats, and is on the ranch that was the location for the film.

Monty – What other projects did you work on in Hollywood?

Didacus – I worked so many projects in Hollywood the list fills several pages. Why, just the names of the projects alone would make a line to the moon and back. (Well, in my dreams). Many of the projects didn’t have names: car commercials, make-up commercials, infomercials, instructionals, educationals, documentaries and forgettable feature films. I also worked a TV pilot about women comediennes for syndication in the days before cable and the Internet (yes, such a time existed).

For a while I had a job as production assistant with Chartoff-Winkler Productions, the company that produced ROCKY and the THE RIGHT STUFF. I liked that. It wasn’t leading anywhere but I met some great people and Bob Chartoff was very generous and kind to me and my daughter. IMAGES – cosmo

Monty – You were a producer on our Last Tiger Expedition, a project to go into the Himalayas in search of a downed WWII plane piloted by Pamela’s uncle. What were some of the things you did on that?

Didacus – The Last Tiger Expedition was one of my favorite adventures right up there with setting up a television station in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia with Monty and some other filmmakers. I used every ounce of bravado to try to make LTE work. Picked up the phone and convinced Pan Am to fly Pamela and Monty to China in search of her uncle Captain Jim Fox who soft-crashed in World War II flying The Hump between India and China.

NASA lent us experimental surveying photographs they were developing for use from outer space. A shuttle flight flew over the crash site! What kismet. We learned how to read the film which was made using a new kind of radar. It could see deep into the earth’s crust but distorted things. Still we found the actual plane—a C-53 perched on a mountainside.

What we didn’t see was that in the intervening forty years a road had been cut that was less than a quarter mile from the crash site. We had fantasies of ferrying up the Mekong River then climbing mountain ranges from Burma to China. The zone was politically hot. So the Chinese declined to let four or five Americans wander near that border. But they understood what and why we doing this. The site had long before been stripped by local tribes. And, there were never any bodies in the plane. That meant Pamela’s uncle probably survived the crash but succumbed to the Himalayas.

In 2002 the Chinese and U.S. governments together dedicated an exhibit about the search for the plane, the trip there by one of Fox’s fellow pilots, and a statue of Captain Fox at the George H. W. Bush Library in Texas. IMAGES — LTE, Statue, etc.

Monty – Why did you choose to study city planning and where have you put that knowledge to practice?

Didacus – I thought long and hard at my career and what I wanted to do with my life. The film industry had taken me half way around the globe, introduced me to so many people and places. In fact, people and places were what I remembered the most. I loved filmmaking but did so little of actual production. People and places—what was it about that that fascinated me? It was how they lived—the differences, the similarities. I loved that.

I took some career tests and they said Urban Planner. I thought, “Cool. What’s that?” Seems it’s a catch-all for whatever you want it to mean. I was interested in why people live the way they do and how could that be improved. So, I applied to the MA in Urban Planning program at UCLA. I suffered through a lot of classes including statistics and probability. I tried to calculate the odds of being successful at this new venture.

After graduation I spent ten years working in Economic Development in the LA area, building affordable housing (I decided it would be neat if I made them energy efficient), and trying to raise the income levels of the entire city. There’s a challenge. The most exciting thing about that town was that one of the senior citizens happen to be first cousin to George Patton. She regaled us with stories about George growing up. Every job has its perks if you look hard enough.

Monty – How has your experience in that field influenced your other work?

Didacus – One day another friend told me that he met a guy that needed someone who understood government development programs. I fit that bill. So, I took a vacation. That took me to three of the Hawaiian Islands reviewing redevelopment programs. I also suggested some environmental systems that they didn’t know about. But politics intervened and the program didn’t go anywhere.

The contact liked what I was doing. So, he invited me to work on a venture in Atlanta, Georgia. What? An adventure? Count me in! I spent five years there trying to make that project take off. It involved gathering, treating and reusing wastewater from septic tanks. My part was reusing the water to grow trees…yah, trees. We were going to grow Paulownia trees in huge numbers and grow an industry. Since 90% of the forests of Georgia had been stripped, I thought this would be a good project. It would have been….but…it never happened.

So, back to California! But not before two weeks in Israel, Turkey and the Middle East. Hey, if you’re going to talk about water, where better than where there is so little of it. I met a lot more people including more Israelis and Palestinians as well as people from around the world. Did I mention that I’m an Israeli?

Haven’t quite solved the water challenge there—but I’m working on it. One of the people I met has tied me to a project in the Jordan River Valley experimenting with my trees there. Her husband also wants to try to use the trees to reforest parts of the desert that his ancestors deforested about a century ago.

Monty – What changes do you see – positive or negative – in the way America’s towns and cities are changing? Is there an ideal international example you’d like to see us follow?

Didacus – A man approached me about working with him on a project in Arkansas. His family has oil, gas and trees—there’s that word—there. Recently he called…and sent a contract. I like that part. I intend to do a survey of that area logging its natural history to see how to reconstruct the prosperity that existed before “we came and made things better.” Of course, I’ll have to make some improvements. Wonder what those will be?

My fascination with how people live around the globe has also connected me to a group who want to build an alternative to the American sprawling suburb. I thought that would be exciting. So, we’ve studied villages and towns around the world trying to glean what the ancients knew that we forgot. For one thing, they could walk to anything that they needed…narrower streets, no cars, multiple use buildings. But we need some new technologies to build village-towns like that now. New technologies. Love it. I’m in.

That means a building with stores, offices, clinics and shops on the ground level and living space above. Just to make it interesting let’s add ways of generating energy on the walls and roofs and grow things on anything the sun can see. I’ll recycle/reuse and re-clean the water over and over before it’s gone. This could be a great, fun place to live.

I work with something that Bobby Kennedy made famous: “Some people say Why; others ask Why not?”

All of this works a lot better if more people can participate. That’s why I’m working with a lot of people to improve personal economics. I’d gladly forgo a dozen billionaires—no matter how generous—for tens of thousands of people with incomes of $100,000 each. That would mean a much bigger Middle Class. And, it would mean a lot more people able to provide for themselves and participate in their communities. Our alternative for sprawl is a village town of 500 acres for 10,000 people, 200 acres will be intensively developed with 4,000 units of housing plus shops etc.; 300 acres of open land in perpetuity. That’s my plan to rebuild America. Oh, we’ll print the building with 3-D full-scale printers. Great technologies. I love toys.

Monty – Clean water is one of the 15 Global Challenges – www.mythicchallenges.com How long have you been working in the water field? What got you interested in and dedicated to it?

Didacus – I’ve been working with water since 1990. I worked with a fish farm in the dessert in SoCal and sold that fish in farmer’s markets around Los Angeles County. I learned a lot about water quality and technologies used to capture potable water anywhere on earth. There are so many ways. But, convincing people to use these things is a huge challenge. Not impossible, but hard.

Why? Because we’ve been taught that there’s only one way to get water. In America it’s by turning a tap. In the deserts of Arabia it’s with a sack into a deep well. But in the American Southwest, native Americans used to stack rocks—huge piles of big rocks. Water would form as dew until it would collect in pools below the mounds. There are other such technologies—they are both high and low techs that draw water from the air.

You ask if that can be used somewhere like Haiti? While it could, Haiti shares an island with over 100 inches of water per year. They cut down all their trees. You can look at the satellite photograph of Hispaniola island and see Haiti all brown on one end and the Dominican Republic all green on the other end. Take a guess what I’d like to take to Haiti. In a perfect world I could cover Haiti with trees in less than five years. But, it’s still Haiti. We’ll see what I can do.

Monty – What ways do you see as the most efficient and effective solutions for our water crisis?

Didacus – You have it right. There is no one way to solve our problems and meet our challenges. The biggest thing that requires is for us to release the past and embrace the future. I know, sounds rather New Age. But, it’s true. We have to let go of the how and why we got here. And, we have to embrace possible solutions—knowing that some are not going to work.

One example is obvious. Los Angeles dumps hundreds of millions of “treated” wastewater into Santa Monica Bay every day because people feel it is yucky to drink water that was once sewage water—the yuck factor. All that water could be cleaned and reused over and over again. That would allow a lot less water to be transferred from north to south. And that would help reestablish the environmental equilibrium.

Monty – What current programs are you enthusiastic about?

Didacus – One of my friends in Costa Rica buys and distributes a bucket filter system to locals. This provides a basic amount of potable water. The challenge has to include ending the source of pollution.

In Rio another friend hooked up with a local group that is now building biogas digesters. This turns sewage into biogas for cooking fuel and the slurry is used as fertilizer to grow food. The result is an improvement in the creek that flows down the middle of the favella. It was an open sewer.

We’re trying to grow trees in Haiti, Ghana, Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia and South Sudan to achieve similar results. The trees provide alternative cooking fuel while filtering wastewater. They also provide forest products for the local and export economy. We call this ‘growing an industry’. That’s what the Paulownia trees are all about. Trees also lower ground temperatures and attract rain–but you have to have a forest.

These village town paradigms also lead to another fascination of mine—getting off this rock. We should be on the moons of Saturn and Jupiter by now. So, first things first. Let’s go to the moon. This time I hope to provide some of the technology we develop for village towns to build cities on the moon, Mars and the moons of our solar system. Why not? Here’s a website for that: http://www.googlelunarxprize.org/prize-details/rules-overview

Monty – Any unusual tips for conservation?

Didacus – Hmm. Shower with a friend. I always liked that one. But the advice is solid—use less. Turn off lights you aren’t using. Walk instead of driving. Buy locally from locals—instead of driving miles for a discounted imported product. This is uncomfortable stuff that most of us say, “Let somebody else do that.” And, therein lies the biggest challenge.

Even walking around your home and adding water conservation methods. Many you can get for free from your utility company. But for it to work, you have to do it.

Next, we can form Community Development Investment Corporations (not all corporations are evil—only the ones that claim they are a person and can run over other people because of their profits and beliefs). Such a fund with 1,000 members contributing $100 or more per month can invest in local ventures that make a difference. For instance, the Tree People install water collecting and reuse systems that could enhance both local schools and parks. They cost about $50,000 per school. Figure out how those schools could pay a minimum amount to keep your fund growing while benefiting from this technology.

Another technology can process waste plastic into fuels.

Another fits into a shipping container that can treat 50,000 gallons of waste water into agricultural quality irrigation water.

The list is like a grab bag of party favors.

Monty – Where can people find out more about what you do? And what other references might you recommend for those who want to further explore the Global Challenge of Clean Water?

Didacus – Just ask me. didacus90035@gmail.com

We can make this happen. But, this is not a solo challenge. It’s a challenge of “All that is necessary for…” you know the rest. That’s why I suggest the community corporations. That format provides a mechanism to act.

Actions get results. Massive actions get massive results.

All of this depends on a basic truth: it is not by just attacking the challenge, but rather by personally developing ourselves into better people…a better you, a better me…that we get a better world.

The rest is commentary.

*****